Landscape Architecture as a practice involves navigating the relationships between nature, the built environment, and specific human needs. As the body of research into these relationships grows and changes, so too does our practice. The potential opportunities for landscapes to enhance and extend our lives continue to reveal themselves, and because of this, it is important that Landscape Architects continue to seek them.

Grant Donald is TDL’s Principal Landscape Architect, and he is a specialist in designing landscapes for our ageing population. Grant has attained a Master of Ageing, and takes special interest in the unique ways in which ageing populations engage with, and can benefit from their environment. Any reasonable person can imagine the positive impact on human health that access to the outdoors can make, but it is the interesting and specialised work of landscape architects like Grant Donald to identify and put into practice the minor details of design that turn research into outcomes.

In his own studies, Grant has identified a number of ways in which outdoor spaces help or hinder individuals in their efforts to maintain their health and happiness as they age. He has done us the favour of outlining some of the key considerations in designing landscapes and communities for older people, to help them age actively. Here is some of Grant’s advice on designing and orchestrating beneficial spaces for ageing people.

Design for Active Ageing

First and foremost, when designers look at designing for older people they need to see spaces as multifunctional and multigenerational, spaces that appeal to as many kinds of users as possible. Including different generations is important, as inclusion in a greater society rather than seclusion and isolation is important for old people. The delivery of barrier-free environments that are truly transgenerational should follow the principles of universal design, defined here by the US-based Centre for Universal Design (in Sawyer & Bright 2007:1):

- Equitable – the design should be usable by people with diverse abilities and should appeal to all users.

- Flexible – the design should cater to a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive – the use of the design should be easy to understand, regardless of experience, knowledge, language skills or current concentration level.

- Perceptible – the design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient condition or the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error – the design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort – the design can be used efficiently and comfortably with a minimum of fatigue.

- Size and space for approach use – appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation and use, regardless of the user’s body size, posture or mobility[1]

Using these guidelines as the road map for good design for older people, we have developed a nine-point design framework that addresses the needs and wants of an ageing population, and provides a creative approach to imagining how spaces can and should be used:

Physical and Mental Rehabilitation

The rehabilitation of an open space focuses on both physical rehabilitation and psychological/mental rehabilitation. Physical rehabilitation areas need to be centered around three major spaces based on the principles of rehabilitating people who require it; strength, balance and resistance. Each space should focus on one of these three so that people at various levels of rehabilitation or at varying levels of physical capabilities can focus on exercising in a particular way. The three spaces should be physically and visually joined together so that people can move from one to the other easily and also see how friends and/or family are progressing.

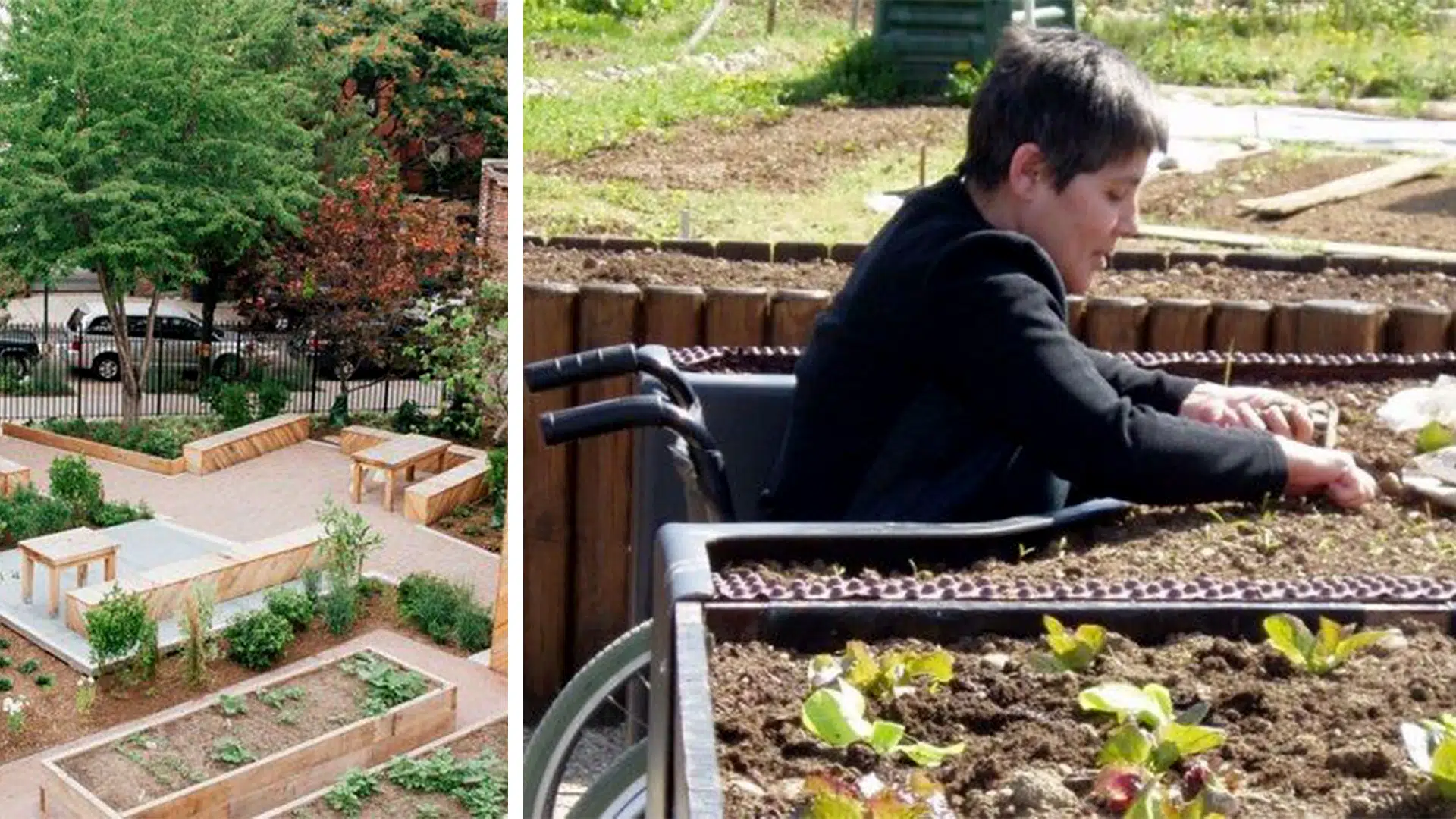

Psychological/mental rehabilitation can and should be considered in several ways. Sculptural elements can reflect features familiar to older people, whether they are sculptures or functional elements like old telephones, old post office boxes, or even old cars. In this way, designers can stimulate memory and help people with longer-term disabilities such as dementia and Alzheimer’s. Areas for horticultural therapy including raised garden beds can maximise the benefits for people who have issues with movement. The beds are often best planted with mainly vegetables and herbs, encouraging ongoing use and cultivation.

Movement and Exercise

Exercise opportunities should be considered throughout any development. These opportunities may take the form of exercise equipment, formalized play areas such as croquet courts and badminton courts, and more informal exercise areas such as a walking track that circumnavigates a park. Large grass areas and large hard paved areas can be provided for activities such as Tai chi, kite flying, etc. In more focused and consolidated exercise areas, children’s playgrounds should be located close by. The sounds and sights of younger generations can help older people feel at home and a part of the broader community.

Integration with Surrounds

The majority of modern built facilities including parks and gardens are designed in isolation, they shouldn’t be. The way in which people travel to, move in and around facilities is of the utmost importance to designers. How a facility sits in a broader context is also very important, outdoor connections through local council land to shops and open spaces must be addressed. Local governments can be asked to review footpaths to cater for people with diminished mobility, integrating wheelchair and pram ramps are also recommended.

Access to and travel between local facilities like libraries, churches, mosques, hospitals, clinics and schools should be considered, maybe a minibus doing a loop between these facilities can be addressed and catered for. All of these elements are important to the life and wellbeing of older people, some for physical reasons (hospital, restaurant), some for spiritual reasons (mosque), some for mental wellbeing reasons (library), and some for family reasons (schools). It should be understood that in the future all of the physical connections to these facilities can be upgraded, and that a shuttle service loop goes past all of these facilities on a regular timetable.

Leisure and Passive Outdoor Access

Leisure activities in gardens and open spaces can occur both in open spaces and undercover. Leisure activities can include chess, backgammon, checkers, sitting and chatting and indoor activities such as cross-stitch, knitting, weaving and watching TV. Leisure activities should be facilitated outdoors wherever possible and reasonable, providing passive opportunities to benefit from fresh air, natural soundscapes and beneficial sunlight levels.

Specialised Amenities

Amenities and facilities provided in gardens should seek to make the garden as comfortable as possible for users. Older people are particularly vulnerable to extreme temperatures, outdoor amenities can be provided to ensure they are able to safely access the outdoors year-round. Purpose-built benches and seats may have heating which can be turned on during winter, cooling fans or misters can be provided throughout the garden during hotter months. Seating throughout the garden should be located every 10 meters, providing ample opportunities for rest. Panic buttons on well-marked bollards can be located at strategic locations to enable facility staff to assist anybody who is under duress. Shade in the form of trees, shelters, pavilions, and arbours should be located throughout. If the garden is to be accessible during the night, then it should be well lit to enable nighttime activities. Drinking fountains should be provided. In sheltered spaces, digital amenities may be provided such as access to device charging, screens providing updates, information, and entertainment.

Community Initiatives

In creating ideal outdoor spaces, one should consider the engagement of the surrounding community and how spaces may facilitate community initiatives. Initiatives may include engagement with local schools, medical services, or vendors to the benefit of all. For example, markets, cross-generational events, or volunteer opportunities may be considered.

Music

Music is a large part of most cultures, and having the ability to listen to your music of choice, to hum or sing songs that call back memories and identity shouldn’t be underestimated. Music also leads to physical activity such as swaying, bobbing and dancing. Locating areas to play music can help with both physical and mental stimulation. This can be in the form of piped music, musical instruments located at different locations throughout an open space, or stages for live music performances. In aged care facilities, it is likely that some of the residents themselves will have musical ability, engaging with them to make music could be a benefit to everyone.

Ongoing Learning

There must be opportunities for older people to continue to learn, grow, and to be mentally stimulated. Continued learning can strengthen their ability to absorb information, stories and ideas. Locating reading stations around a facility, installing bird feeders and guides for identifying local birds, placing plaques and notice boards describing the plants in a garden and where they came from and what the can be used for, are all creative ways of getting people outside and stimulating their minds. Access to art, conversation, and stories can be of tremendous value to the aged, must create opportunities to learn and keep growing.

Details

When the great German Architect Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe said “The Devil is in the Detail” he was talking about the importance of understanding the smaller details of a project rather than the conceptual ideas. That is really what gardens for older people need to address. Understanding the little things about older people is the most important element of the whole design process. Following are some examples of some of the important things that need to be addressed when detailing spaces for older people.

- Height of old people – A garden’s key elements that are used and interact with people have to be designed around the human form. The average height of men worldwide is 178cm, women 164cm. As we age we get shorter – on average men get 25mm shorter and women 50mm shorter. This being the case, any chairs/seats, tables, handrails, handles, etc need to be adjusted down to fit older people, off-the-shelf seats and chairs do not facilitate comfort or ease of use for older people.

- Vitamin D Deficiency and Sunlight – The Cancer Council’s initiatives over the last 40 years to ensure that people limit exposure to the sun have had many benefits, but there could also be a downside. Australia’s older people have among the highest rates of vitamin D deficiency in the world. Vitamin D deficiency can lead to rickets and Osteoporosis. Limited access to sunlight can also affect mood, and alter sleeping patterns, efforts should be made to ensure older people can safely access optimal levels of daylight.

- Animal assisted therapy (AAT) – is a type of therapy that is becoming more recognized in aged care facilities, exploring opportunities for having permanent spaces for birds or rabbits, or visits from other animals such as cats or dogs would require places that could accommodate them. Increasingly, domestic animals are being recognised as a legitimate way of soothing people and facilitating better quality of life.

- Colour and Smell – Color and smell stimulate parts of the brain not reached by intellectual activities, and even those with little cognitive ability seem able to sense the tranquility and beauty of a garden on a precognitive, affective basis. Outdoor spaces provide opportunities for pleasant smells such as fragrant plants and fresh air. Plant materials should be used to create opportunities for visual, tactile, and olfactory experiences. The principles for the selection of plant materials include: providing contrast of light and dark, using bright colors, varying the size of plant materials, incorporating recognizable themes, and relating the content to the backgrounds of the residents. Changing plantings can provide seasonal highlights as well, helping to generate cues for the passage of time. Outdoor spaces should offer “reality cues” by reminding confused and chronically ill residents of the season, time of day, and weather (Carpman and Grant 1993)[2]

- Vision – One aspect of designing signage for outdoor use by aged people is that signs at or slightly below eye level are needed to compensate for spinal changes, which can produce dizziness when an older person looks upward. (Panero and Zelnik, 1979)[3] Reduction in peripheral vision means that very large graphics will be out of the visual field (Bowersox, 1979).[4] Level changes or steps need to have a high hue and value contrast because of diminishing sight abilities. Designers should be aware that overly busy, or high contrast designs on flat surfaces may be misinterpreted as level differences, any graphic elements at ground level should be carefully considered with vision in mind.

Further Reading | Works Cited

[1] Sawyer, A & Bright K (2007) The Access Manual, Auditing and Managing Inclusive Built Environments, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. Cited in Matthew Carmona, Steve Tiesdell, Tim Heath & Taner Oc (2003)Public Places – Urban Spaces p157

[2]Carpman, J. R. and M. A. Grant (1993). Design that Cares: Planning Health Facilities for Patients and Visitors. Chicago: American Hospital Publishing. Cited in Clare Cooper Marcus, Marni Barnes (1999) Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, p.409

[3] Panero, J. and M. Zelnik (1979). Human Dimension and Interior Space. New York: Whitney Library of Design, Watson-Guptill Publications. Cited in Clare Cooper Marcus, Marni Barnes (1999) Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, p.414

[4] Bowersox, J. (1979). “Architectural and Interior Design.” In L. J. Wasser, Long Term Care of the Aging: A Socially Responsible Approach. Washington, DC: American Association of Homes for the Aging. . Cited in Clare Cooper Marcus, Marni Barnes (1999) Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations, p.414

thank you!

Thank you for taking an interest in the role of landscape in active ageing. If you’re interested in learning more about our commercial design work, or how landscape architecture can improve our health and communities, contact us with the button or number below. Stay tuned for part 2 of this discussion by subscribing to our newsletter, or reach out to us and speak with Grant directly to learn more.